Twenty years ago, on June 7, 2000, the Ohio Supercomputer Center (OSC) announced the creation of the Young Women's Summer Institute—a summer educational program for middle-school girls in Ohio designed in response to the documented lack of interest in math, science and engineering among girls. This unfortunate situation was translating into the low participation of women in the science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields, and in particular, information technology.

OSC added YWSI as a partner program to Summer Institute, a two-week residential program started in 1989 for high school students—boys and girls—in their freshman, sophomore or junior year. YWSI was designed to pique the interest of girls before they hit high school, when it might be too late to develop a STEM interest, and to provide an all-girls environment for undistracted learning.

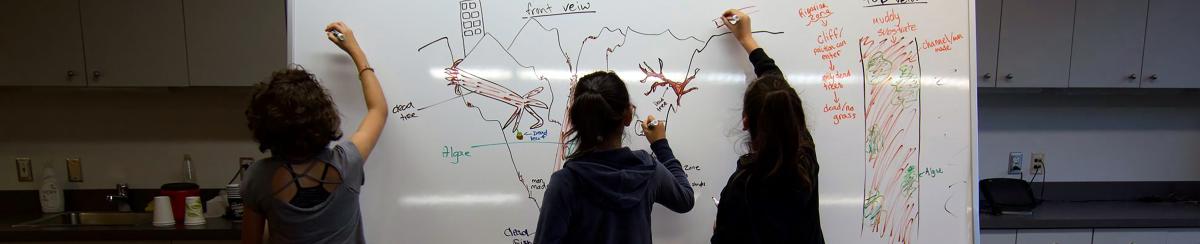

For two decades now, YWSI has been helping girls develop an interest in these subjects by allowing them to work on a practical, interesting scientific problem using the latest computer technology.

Annual surveys and longitudinal studies of YWSI participants conducted in 2004 and 2010 indicated that the program positively influenced them. During the more recent study, about 74 percent of the students who participated in YWSI indicated that their interest in science and/or math classes increased since their participation in the program; more than 75 percent of the participants conveyed they had greater confidence in math and science classes since participating in YWSI.

One of OSC’s STEM-education success stories was explained in detail just a couple of weeks ago in this blog by 2013 SI participant Elizabeth Grace, who recently graduated from college with a degree in chemical engineering and has just begun a job as a process R&D engineer at Dow Chemical.

There are many more SI and YWSI success stories like Elizabeth’s. Yet, while YWSI staff and volunteers hope to nudge a good percentage of the 15-20 girls who participate each year into STEM careers, they realistically understand that those numbers alone won’t dramatically affect national numbers. In fact, the challenge may be growing.

A recent article, “The Gendered History of Human Computers,” in Smithsonian Magazine documents this disturbing workplace trend, citing examples of some hiring managers who doubt women’s technical chops, some who question women’s natural abilities in STEM and others who chase them out of the field through harassment and intimidation.

“Not everyone in the field is antagonistic to women, of course,” suggests author Clive Thompson. “But the treatment’s bad enough, often enough, that the number of women coders has, remarkably, regressed over time, from about 35 percent in 1990 to 26 percent in 2013, according to the American Association of University Women (AAUW).”

That trend cannot be allowed to continue, if the United States is going to compete with other nations, like China, India and others, that seek an economy boosted through technological advances.

“A well-trained STEM workforce is crucial to America’s ability to innovate and compete on a global scale,” said Steve Gordon, a former senior education specialist at OSC and long-time director of the summer programs. The AAUW today still agrees with his assessment:

“In less than 10 years, the United States will need 1.7 million more engineers and computer scientists. Adding women strengthens the talent pool and leads to better creativity, innovation, and productivity.”

YWSI aims to help its participants understand the professional and societal challenges. As part of the program, the girls learn first-hand about the many exciting and interesting roles successful women play in these fields. They meet throughout the week with female technicians, scientists and professors who speak to them about opportunities and obstacles in the STEM world and how they were able to persevere.

As the AAUW concludes, “increasing the representation of women in engineering and computing is good for women and good for business.”

All photos YWSI 2019: Credit Anam Afroz